Otis Robinson speaks with Dr Sahar Arshi, research fellow at the University of Leeds, about a university-led project to develop software capable of digitally communicating hand feel across the globe.

Hand feel is key to garment fashion design and even a product’s success on the high-street. Investigating a fabric through touch is one of the first things textile manufacturers, designers and end-users tend to do.

Since designers and manufacturers must remain considerate of style, drape and fit, they consequently need to know the properties of a fabric before developing a product; while elsewhere, shoppers in-store prioritise the feel of a garment second only to its appearance. This touch-reliant process helps to confirm a purchase is the right decision.

But now that ecommerce has overtaken industry and the high-street – opening a vast geographical distance between many designers, manufacturers and end-users – there’s a problem. The opportunity to physically engage with a product has been lost in favour of digital transactions and home deliveries. When designers or end-users receive a sample or garment and feel the fabric for the first time, it’s likely they would prefer something a little different.

Fabric samples end up flown from one corner of the globe to the other, while product returns for online retailers experience a similar back-and-forth – these returns are expected to reach a value of GB£5.6bn by 2023 according to reports by analytics company GlobalData. This cyclical process – order, deliver, return, reorder, deliver – requires water and energy for producing samples, fuel for air and land deliveries, and thus is both incredibly lengthy and detrimental to the environment.

In search of a solution for this pertinent issue is Dr Sahar Arshi, a research fellow from the School of Design at the University of Leeds, UK, and along with project lead Professor Ningtao Mao, is a researcher in a project titled The Digital Communication of Fabric Properties. Part of the Future Fashion Factory (FFF), a Creative Industries Clusters Programme that supports innovative projects in the fashion and textile industry, the two-year project intends to develop a piece of software that will facilitate the virtual communication of material hand feel from one location to another, no matter where the end-users are located on a map.

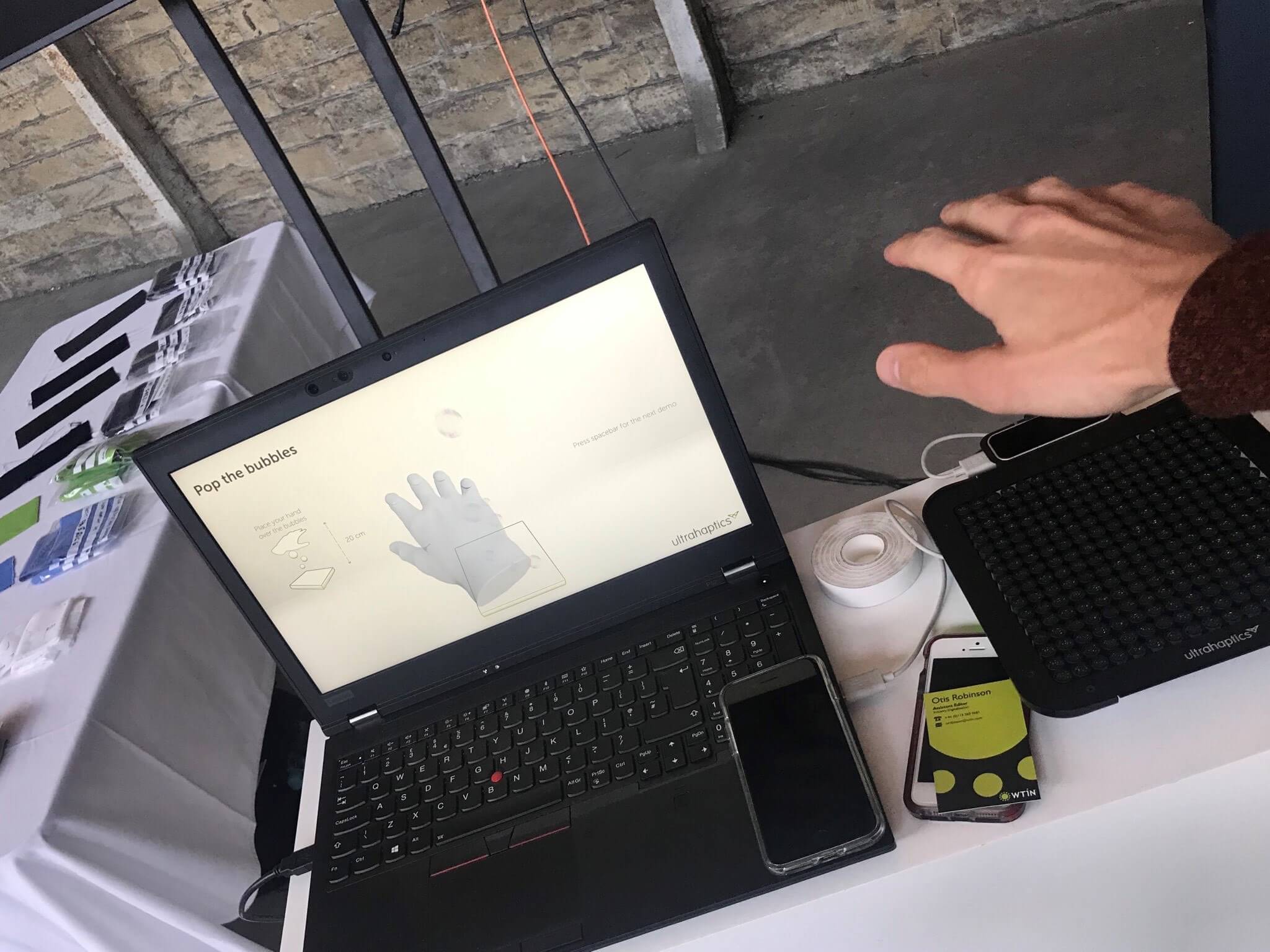

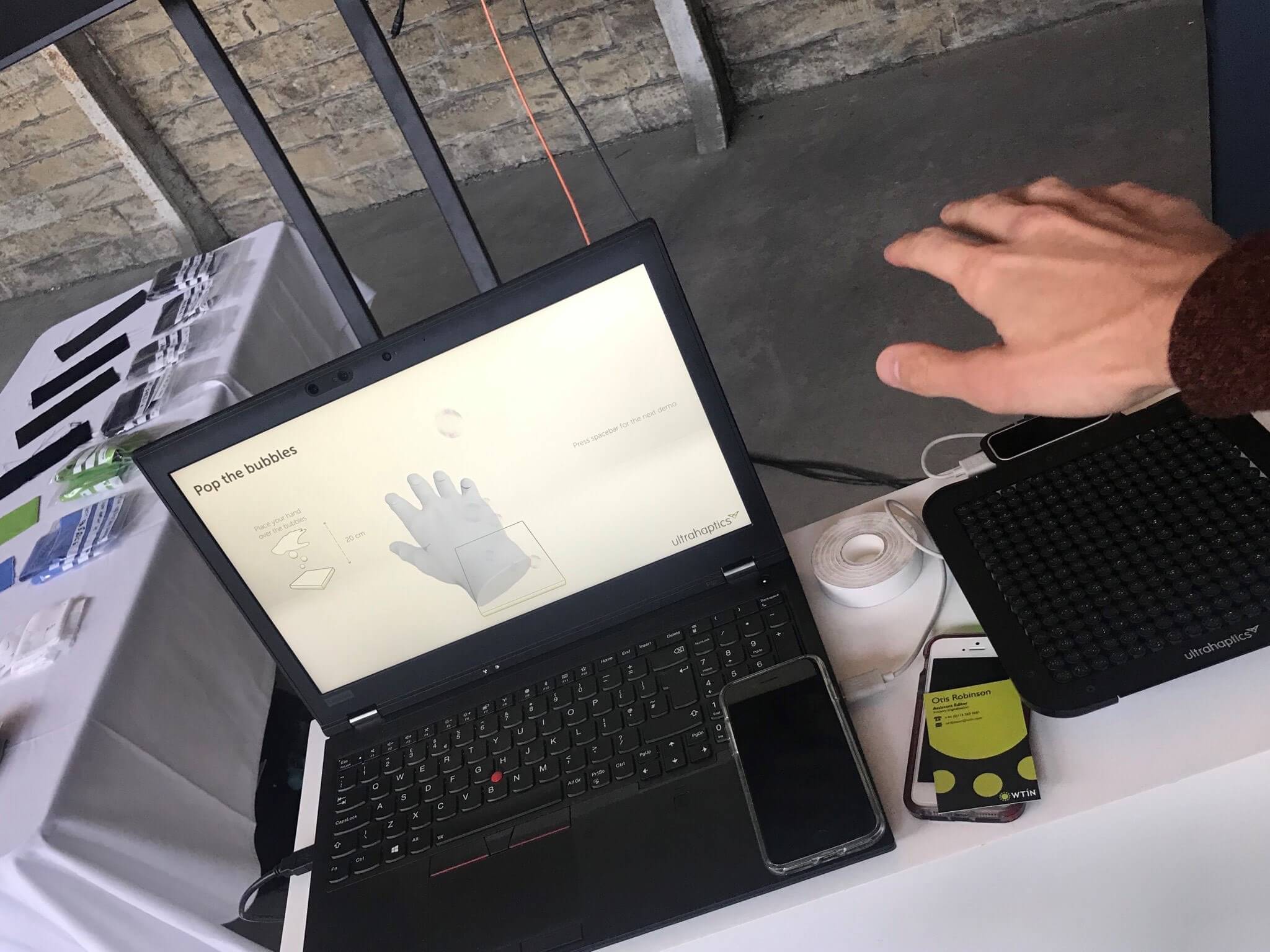

The concept is introduced at the FFF’s first annual showcase event in October – titled Innovation and Heritage: Future Fashion Factory Year 1 Showcase – where Arshi stands beside a pedestal, a laptop and a strange square device, ready to share details of the project with attendees.

Technologies

The planned research intends to use established haptic technologies developed by tech company Ultraleap, and utilise ultrasonic waves to simulate the feeling of fabric handle, Arshi says.

On a table at the event – which takes place in an attic room in Salts Mill, Saltaire, UK, a former textile mill turned art gallery – the black pad sits unnoticed beside the laptop. Arshi switches the pad on and selects two existing examples from the Ultraleap system for delegates to test out – one titled ‘bubbles’ and the other ‘forcefield’. I place my hand a few inches above the device; the latter example feels like a thin, buzzing wall. It’s a bizarre experience to feel an object that the eyes cannot see.

Mao and Arshi plan to wield this tool as part of their research and will utilise other technologies, too. But for the purpose of demonstrating the project goal, this specific haptics pad is used. The technology consists of clustered ultrasonic transducers, and the device uses a motion sensor camera to follow a user’s hand while an algorithm generates specific ultrasound waves to create the sensation of touch.

“The palm of the hand has four types of mechanoreceptors,” Arshi explains. “These receptors are sensitive to low frequency or to high frequency vibrations. We intend to utilise this Ultraleap system in the future through an algorithm to create the sensation of the feel of a fabric."

But touch is a subjective experience, so how can a piece of software be developed to mimic the feel of cotton, or polyester, or more?

Until now, Arshi confesses, it has been difficult to quantify – or, put into readable data – the feeling of material that is smooth, rough, spongy, flexible or stiff. Another University of Leeds project on show at the event, led by Professor Chris Carr, even specifies that hand feel is experienced differently by each individual, and is dependent on the level of moisture in their skin and the environment around them.

But Arshi and Mao make use of a unique tool invented by the latter that puts the hand feel experience into objective data that is readable by a computer.

“There is machinery at the University of Leeds called Leeds University Fabric Handle Evaluation System (LUFHES),” Arshi explains. “This [patented] system, invented by Professor Ningtao Mao, is able to objectively quantify – or digitise – fabric tactile properties to help the entire fashion supply chain.”

The machine deforms fabric – by buckling, applying torsion and friction – to measure the energy that is required to do so. Arshi explains that LUFHES can then quantify properties such as softness, flexibility, sponginess, formability and more, to apply numerical characteristics to a certain fabric. According to tests conducted at the University of Leeds, this objective measurement successfully aligns with subjective experience.

“We performed a subjective assessment of fabrics (for hand feel properties) and we compared this to the objective assessments made by the LUFHES system. They [corroborated] each other, which means that LUFHES is able to quantify fabric properties and tactile properties very, very effectively.”

The measurements obtained from LUFHES and other tools will be implemented along with the behaviour of the ultrasound transducers of the haptics pad. Once this connection has been forged, the project team can “manipulate and play with the parameters to generate the texture of fabric”. With the project now well underway, the researchers have begun developing this bridge between the two technologies.

“The first step is that we have to be able to find more fabric characteristics to describe the fabric itself and we have to be able to map these properties – these measurements – to a frequency domain,” Arshi says. In layman’s terms, the team needs to develop the language that will communicate the feeling of cotton, for example, through an ultrasonic wave. “We also need psychophysical and neurophysiological knowledge, because the tactile properties [experienced by] human beings are very difficult to describe – people investigate fabric using their subconscious, so it is subtle to describe what they really feel.

“If we can link this measurement with subjective evaluation by humans and see how we can actually map them to the [frequency] domain, then that would be really helpful. […] I’m working with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in order to communicate the fabric properties digitally.”

Applications

Once the project is completed, Arshi and Mao plan to patent the technology and bring the product to market for manufacturers and retailers. Its applications in industry circle back to design and retail spaces. Designers in one location could use the haptic tool to browse fabric samples sourced elsewhere, cutting the time and cost associated with sending samples that might have traditionally taken three-to-five days to arrive. Arshi also adds that online shopping can become a much more ‘fun’ experience for customers and the technology may tackle economic issues hitting brands and retailers.

“It [will] make things much easier for people and for end-users – the people who do online shopping. They can investigate fabrics and [examine], before they touch the real fabric, whether it is suitable for their purpose, whether they like it or not. There would be such a reduction in returns.”

Professor Stephen Russell, director of the FFF, adds: “For consumers, there’s the potential for new immersive experiences in e-commerce, offering shoppers the chance to interact with a fabric before they place an order, and reduce the number of garments being returned each year.”

Although haptic pads are a considerably expensive tool for end-users to get their hands on, Arshi believes this technology will only become increasingly more accessible in the future. And, despite its unique retail and design potential, Arshi suggests that its sustainable benefits are another primary driving force.

“It would help with global warming,” she says. “It will save posting time [and resources] and save so much on the packaging [and return] of products.”

Evaluation

Under FFF guidelines, the project has direct links to industry. This in-turn proves its valuable use in practice. Local company Advanced Dyeing Solutions Ltd (Roaches International) is also working on a related FFF project with Mao.

This targeted change set to be established by the project is accredited to the ethos of the FFF: “I’m happy that the Future Fashion Factory supports innovation and tackles challenges in the industry,” Arshi says. “That is quite impressive.”

At the event, which features projects lining the walls of Salts Mill’s rooftop room, Arshi also made note of the unique work in progress alongside the haptics project: “I am also very impressed by the work of other [FFF] researchers in the area of textile and fashion. It is quite impressive how work in one area impacts work in another area. I learned a lot from the event and people I talked to. It was a great experience.”

Russell concludes by sharing his thoughts on Mao and Arshi’s work, summarising the shared sentiment and excitement among those working on the project: “The technology has potential to speed up the process of communicating the tactile properties of fabrics between buyers and suppliers, as well as reducing waste.

“This could lead to improvements in agility and the sustainability of fashion supply chains.”

Have your say. Tweet and follow us @WTiNcomment