Per Stenflo, founding partner of Imogo AB and its spray dyeing technology, talks to Madelaine Cornforth about the need for a technological transition in the textile dyeing market.

The textile industry, and the dyeing industry in particular, needs to undergo a transition towards a more sustainable production supply chain. Imogo AB (Imogo Tech) is a Malmo, Sweden-based company aiming to transform the traditionally wasteful and pollutant dyeing industry with its Dye-Max spray dyeing technology.

Developed at the Swedish Textile School by a team with textile processing technology experience, Imogo is a newly founded company that focuses its attention around sustainability and efficiency. “This is basically the reason why we started the company – because this technology has such promising opportunities and it can really make a difference,” says Per Stenflo, founding partner of the company.

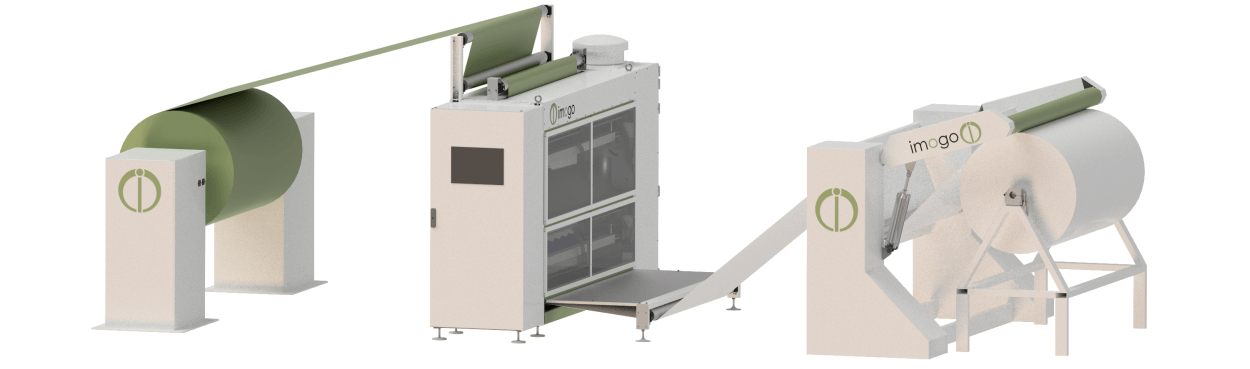

Imogo has partnered with ACG Kinna to build the first Dye-Max line and is present at the ACG Kinna automatic stand at ITMA Barcelona. The full prototype Dye-Max line was made available from the first half of June. Full scale testing will start immediately, taking place throughout the summer and into Q4 2019, and Imogo plans to bring in customers for testing on an industrial scale.

While still at the prototype stage, and with a first full-scale line currently under construction and due to be demonstrated this Autumn before delivery, the Dye-Max, according to Stenflo, promises to slash the use of fresh water, wastewater, energy and chemicals by as much as 90% compared to conventional jet dyeing systems.

Technology

The Dye-Max is a reel-to-reel line where Imogo has shifted out a padder or other application methods to a spray applicator. Once the fabric has been spray-dyed the dye is then fixated onto the fabric. Stenflo says that all these technologies are pretty well known in the industry but the combination of how the company uses technologies together, along with some special features, makes it efficient and “also makes sure that we can reach the savings that we have proclaimed that we can.”

According to Stenflo, the technology has such a huge reduction of water because the spraying technology only sprays on the exact amount of water that is needed to carry the dyestuff onto the fabric, exactly where it is needed. “That’s very different to how traditional methods are done today where there’s a lot of water carrying the dyestuff and most of it is actually wasted,” says Stenflo.

The application unit consists of a closed chamber containing a series of spray cassettes with precision nozzles for accurate and consistent coverage, in combination with the patented Imogo pro speed valve that controls the volume to be applied. The chamber is equipped with an exhaust system and droplet separator to ensure that the environment around the unit is free from particles.

“The spray cassettes are a key part in the Dye-Max line,” says Stenflo. “There is one set of spray cassettes for each of the three separate dye dispersion feed lines and they can be easily exchanged without the need for tools in less than a minute. This allows for extremely fast changeovers between different colours without the need for cleaning. As the spray cassettes are removable, all maintenance can be performed offline. After applying the dye dispersion, the fabric is rolled onto a shaft and moved to the autoclave for deep dye fixation via heat and pressure.

“At the same time, the low liquor ratio and the spray process require considerably less auxiliary chemistry to start with, and all of it is used in the process, which also greatly reduces the production of wastewater, with only 20 litres being required for wash at changeovers,” he adds. “The low liquid content in the fabric meanwhile minimises the energy needed for fixation.”

There is no specific pre-treatment needed with the technology, apart from the fact that the textile has to be cleaned to get rid of any oils or dirt that could negatively impact the dyeing process. This is the same process as would be required in traditional dyeing methods.

After fixation, the only post-treatment required, according to Stenflo, is rinsing. He says: “There will be a small amount of dye left on [the textile] that’s not perfectly fixated that needs to be rinsed out. Apart from that there are no specific or special treatments necessary,” meaning that no chemicals are needed for pre- and post-treatment processes.

Also, the rub-fastness, colour-fastness and hand-feel of the finished product are similar to that displayed in traditional dyeing. Stenflo says: “The hand-feel is very good, very similar to what you would have in a traditional dyeing method and [the] colour-fastness is excellent.”

However, the company does not yet have results for large volume production, but it is in the process of scaling up the technology: “To this point we have been limited in run sizes – our largest run is 200m, so we don’t have the large volume experience yet,” he says. “It’s right now in the process of being scaled up. There are questions left to be answered once we have the industrial-sized dyeing and we can do these tests in a more realistic fashion than the laboratory scale.”

Right now, the Dye-Max technology is being used on polyester, but the company has performed a lot of tests on other substrates such as cotton, where it has seen “very good results with reactive dyes,” says Stenflo. “As well as polyester, this is one of the things that we are going to be developing as well,” he continues.

The same dyes can be used as any other traditional dyeing method, such as reactive dyes and disperse dyes. “Basically, any dye that we use today can be used on the system,” says Stenflo. “The difference is only the method of applying it. We don’t change the process in terms of how it works. So, we can use the same dyes and we have good results with all the dyestuff that we have tested with, but our focus right now is on polyester – the most used fibre in the world.”

Industrial vs. sampling

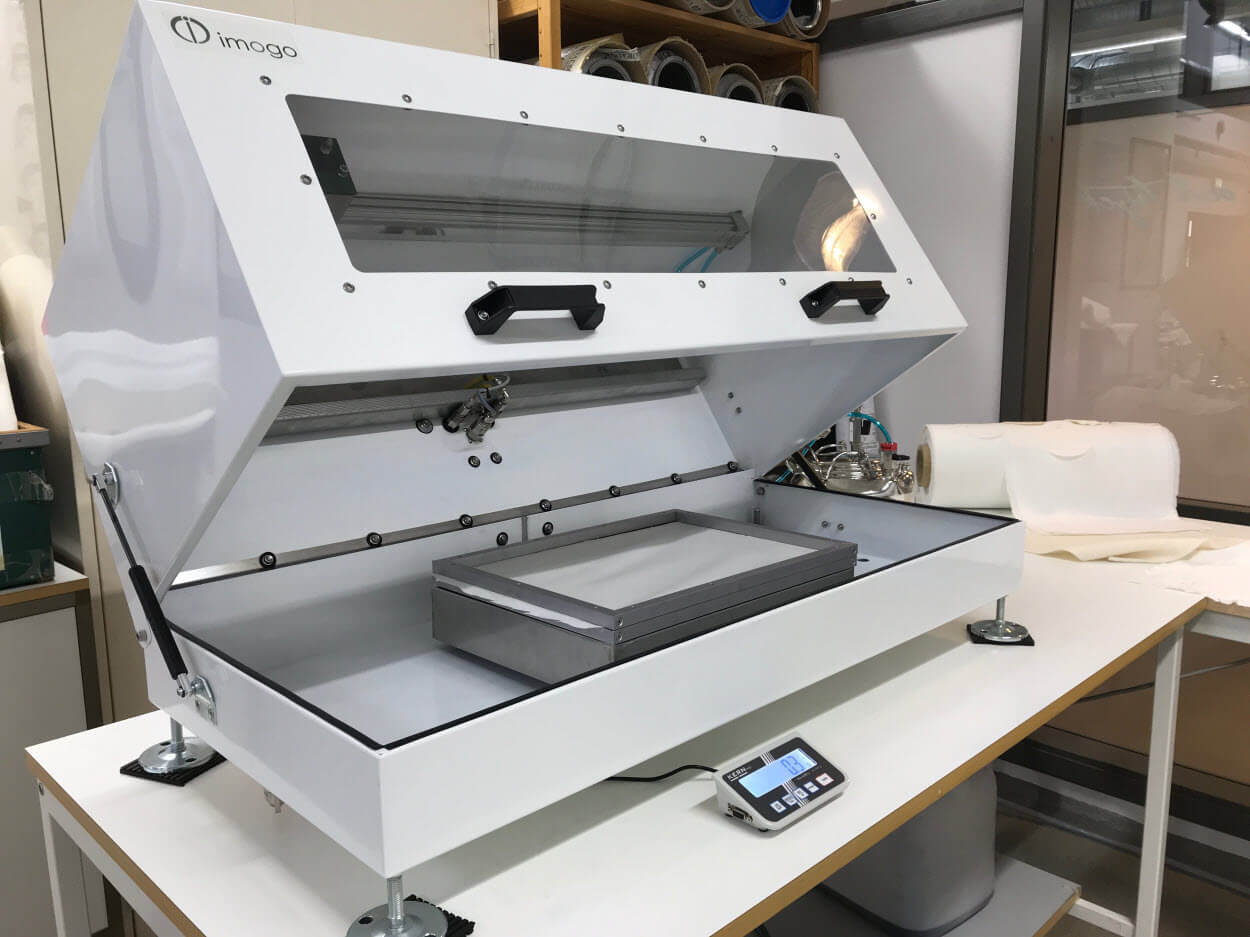

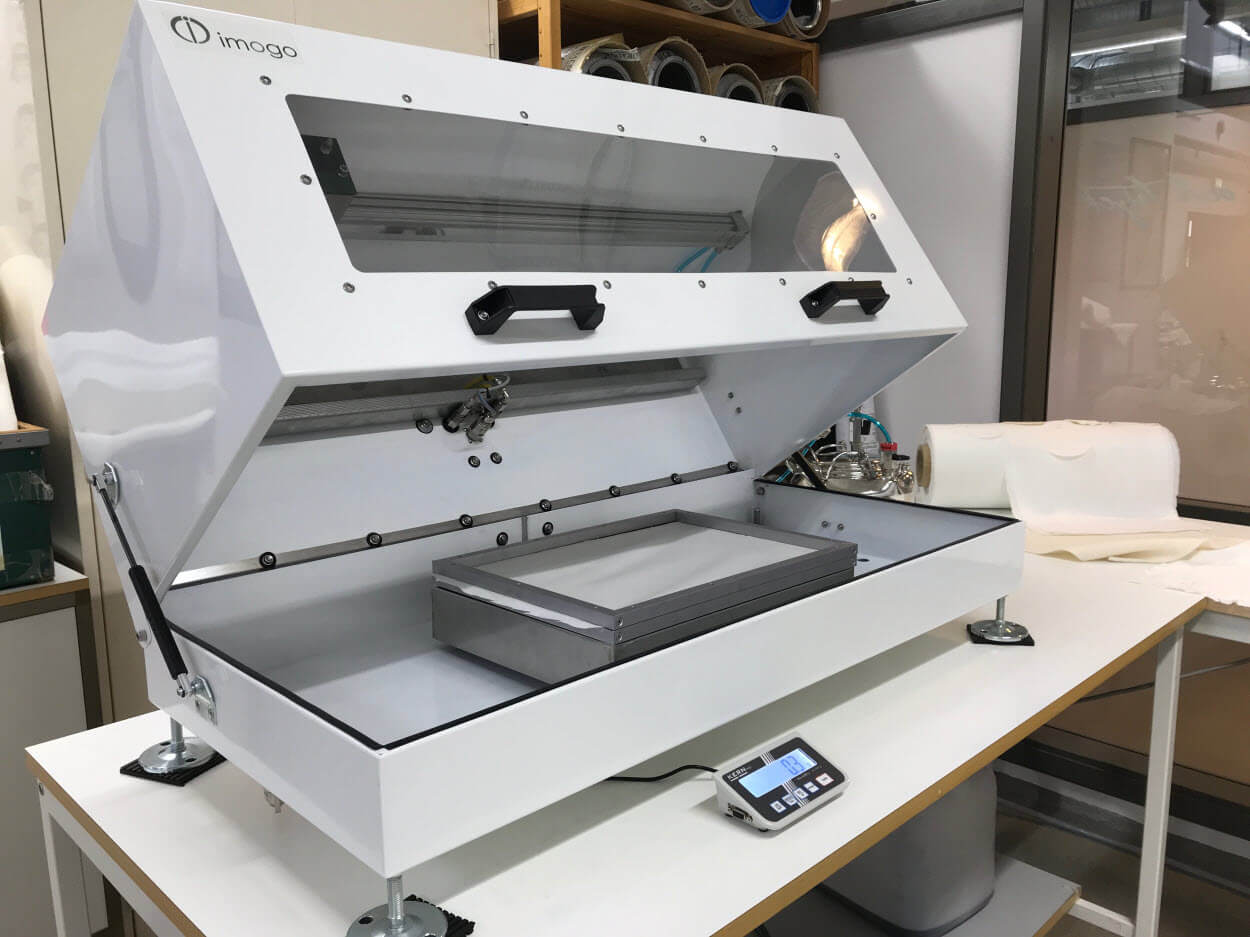

The Dye-Max has a working speed of up to 50m/min with the practical speed determined by the fabric weight and application volume. The application volumes and speeds can be pre-determined by running tests in the Mini-Max laboratory unit.

“With the Mini-Max it is possible to run miniature production tests to set the precise colour recipe,” says Stenflo. “This frees up valuable production time by avoiding wasteful pre-runs. The user simply sets the recipe with the Mini-Max and transfers the parameters to the Dye-Max recipe database for the system to be fully production ready.”

One of the biggest benefits for users of the Dye-Max is the savings that it can bring, in terms of monetary value and the environment. Stenflo says: “We consider ourselves environmentalists and the savings and the sustainability is where the difference is. The big difference is the savings for the environment with all the less resources that’s required and that translates into monetary savings”

He adds: “Everyone is concerned about the environment and this is a big focus but, to enable sustainable approaches, there has to be the business-sense in doing it in a more traditional way of saving and becoming more efficient. So, our technology not only saves environmentally but can save a large amount of money for our customers.”

Additionally, less labour is required with spray applications compared to traditional dyeing methods and the flexibility of production can be increased. “Most of the traditional dyeing methods are designed for large batches and the fast-fashion trends and the small samples are a problem to everyone today,” says Stenflo. “With our technology we can, in a very efficient way, run very small sample lengths of a few dozen metres compared to the volumes that are normally required to make it efficient today.”

As both samples and industrial volumes are a possibility, this opens-up a large number of markets for the technology. The smaller runs are useful for the European and US markets that are currently experiencing reshoring. The industrial volume batch sizes are ideal for large manufacturing markets such as China, Indonesia and India. Stenflo comments: “While Europe is very interesting to us, our big market in the future will naturally be Asia, Turkey and areas like that.” However, he notes that the company’s first systems should be in Europe in order to support reshoring and sustainability in European markets and then, with good feedback from Europe, Imogo can be introduced to the industrial markets in Asia and the Middle East.

In terms of sustainability, the technology’s impact will be most felt in industrial markets such as China, with legislation and taxes on wastewater increasing. And it is not only China that is experiencing this, but Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh and India as well. “All the areas where a large amount of the textile we use in Europe is manufactured are struggling with this,” says Stenflo. “They’re all under enormous pressure to improve sustainability efforts. This is where we see our technology can make the biggest impact on the environment.”

Whether industrial or for sampling, the same technology is used. “It’s the same set-up if you run large batches or if you run only sample batches,” says Stenflo. “For Europe obviously the sampling is a very interesting possibility. Logistical costs and the transport emissions are one of the big areas of interest for customers in Europe.”

Challenges

New technology though, does not come without its challenges. Although the technology development with the Swedish School of Textiles has gone smoothly, Stenflo realises that the company’s biggest challenge may lie ahead.

He says: “There are always risks and unknowns when you scale-up a small-scale laboratory set-up to an industrial scale.” However, the industry is ready for this type of application, considering the current economic and political landscape. With the industry previously being so closed and traditional when it comes to new technology, Stenflo notes: “I am surprised at how open-minded the industry is today. Everyone knows there has to be changes and everyone is looking for what is going to be the next way – how will we meet these regulations? How will we meet the customer’s demands on sustainable manufacturing?

“Everyone is ready for this. Then of course there’s always the challenge of who will be the first and who will be the pioneers of this technology. The feedback that we’ve had so far is only positive and it’s very encouraging.”

Imogo has conducted full testing of the system at the University of Borås in Sweden and has been more than satisfied with the quality which has been achieved. “There can be no doubt that the textile industry will transition to more sustainable production processes and it’s not a question of if this will happen, but what will replace the currently established process technologies and how quickly new solutions will be accepted,” concludes Stenflo.

For more information on Imogo and the new technology visit https://imogotech.com/

Have your say. Join the conversation and follow us on LinkedIn