How personalisation tech can eradicate homogeny in fashion

By Otis Robinson

In exploration of personalisation, Otis Robinson summarises the technologies and challenges associated with the trend, the manufacturing models textile leaders may soon use to revolutionise the industry, and the ways manufacturers might engage with end-users in the future.

As Industry 4.0 concepts proliferate and technologies evolve, the end-user follows: modern manufacturers now face the demand for consumer personalisation within the textile manufacturing chain, and tech innovators have been fast to heed their calls.

Black hole

“There’s a big black hole in fashion. Manufacturers are producing [products] that nobody cares about, nobody needs,” says Andrey Golub, co-founder, chief executive officer (CEO) and chief technology officer (CTO) of ELSE Corp, a tech solutions start-up company situated in South Europe. “As fashion goes in that direction, […] the only goal is to produce as much of it as it can.”

Although seemingly pessimistic in his view of contemporary fashion trends, Golub is actually one of many fashion industry vigilantes queuing up to take a hit at over-productive, energy-consumptive, homogenous fast fashion trends that operate under mass production manufacturing models.

Since the dawn of the Second Industrial revolution, rapid industrialisation and technological advancements have enabled such mass production of garments, apparel and footwear in the fashion industry. But clothes produced within this new mode of manufacture are no longer made with the interest of the singular consumer in mind as they once had been; no longer tailored to the specific shape of an individual body; and no longer designed on an individual basis.

Mass produced clothing was, and remains today, conceptualised with generalisation in mind – shaped according to the general fit of the human form, derived from anthropometric study – which means manufacturers could repeatedly churn out the same garment. Forging a gargantuan fashion retail industry and economy, this rapid, repeatable and revolutionary manufacturing method served a considerably damaging double purpose: mass production inadvertently worked to homogenise fashion trends, set an energy-consumptive standard for production, and pump landfills with massive amounts of waste apparel. But what solutions are available for this pervasive threat to fashion individuality and the environment?

Mass customisation

The trick is to turn the attention back toward the individual needs of the end-consumer, industry leaders suggest. So birthed was ‘mass customisation’, which forged the bedrock for new, on-demand manufacturing processes.

B Joseph Pine, author, speaker and management advisor, is said to have popularised the term ‘mass customisation’ in his book Mass Customization: The New Frontier in Business Competition, published in the early nineties to immense popularity. He defined it as “developing, producing, marketing and delivering affordable goods and services with enough variety and customisation that nearly everyone finds what they want”. This is supported by C M Eckert et al in the paper ‘Mass customisation, change and inspiration – changing designs to meet new needs’, where Eckert says mass customisation (or agile manufacturing) involves the modification of products or services to meet the requirements of ‘particular groups of customers’.

Pine’s concept remains pertinent to this day. Within the typical high-street setting, customisation can be found in coffeehouse chains, for example, whereby customers can augment beverages to their dietary or preferential requirements.

Similarly, mass customisation in the textile industry tends to involve minor design alterations that occur late in the manufacturing process. For example, the web-to-print capabilities of digital print houses allow users to upload patterns, images or colours for print application on a variety of textiles such as apparel (hoodies, T-shirts, shoes, etc) and homeware (cushion covers, bedsheets, curtains, etc). This mode of manufacture works excellently for miscellaneous holiday-based gifts, promotional merchandising and apparel-based marketing.

Though, on the surface, this model appears benevolent – homogeny seems to be stifled because consumers are able to individualise garments, and because this apparel is made-to-order, it appears to help reduce overproduction – but it actually fails with regard to energy-consumption and overall individuality.

Within this model, garments tend to be pre-made remotely by mass production facilities, bought by digital print companies and stored in their warehouses ready for customised printing, meaning mass customisation actually supports the success of mass production because companies rely on cheap, mass-produced, homogenously-styled apparel to store, print and sell to their end-users. And, although developed technologies such as digital textile printers and web-to-print interfaces make a valiant attempt to customise these products, individual changes are often minimal and limited.

But Golub represents one of a many hopeful companies that intends to implement real change through what he touts as ‘personalisation’.

Personalisation

The term personalisation is commonly used to refer to the recommender systems embedded in e-retailer sites and social media platforms, which use user data (such as search history, location, weather, online activity, etc) to influence individual customer purchases. In fact, 43% of purchases are influenced by these personalised recommendations or promotions, according to data presented by Nosto at the Growing Your Online Funnel webinar. But its meaning is changing to suit growing Industry 4.0 concepts within the textile and fashion industry.

“There is quite a lot of confusion in marketing language about personalisation and customisation,” Golub confesses, “but we have a vision to separate [the two terms].”

The ELSE Corp co-founder clarifies that the company defines true personalisation as a product that is modified exactly for the consumer with sole individuality in mind. But customisation, Golub adds, is more of a ‘co-design’, which means changes are part of the brand’s design framework.

An example would be those aforementioned web-to-print companies, whose manufacturing processes are reliant on the expectation that customers only want to add mere printed images to their clothes, and whose platforms only offer a select few areas, colours or substrates for printing. In stark contrast, personalisation would offer a layered experience, Golub suggests, that consists of multiple changeable qualities on an item with regard to materials, colour, embellishments, style and more.

“These are two completely different ways of [production],” Golub explains.

Golub’s distinction is supported by press, too. In an article for the Euromonitor International by Kseniia Galenytska, ‘personalisation’ is positioned as the ‘antidote to the homogeny of fast fashion’, with reference to declining ‘identity and true personal style’ and millennial disillusionment at the homogenous styles of fast fashion.

This is also supported by statistics: according to research by Deloitte UK, 43% of 16-24 year olds and 46% of 25-30 year olds are “attracted to personalised goods and services”, while 71% of interested customers “would be prepared to pay a premium” for personalised products. The study determined that 25% of customers were interested in personalised holidays, 19% in personalised clothing and 18% in personalised furniture. However, Deloitte elaborates that demand for such custom “runs counter to the dominant” mass distribution model.

Although brands already allow consumers to customise products with mass customisation, Galenytska highlights a potentially up-and-coming new era where personalisation can occur at a much grander scale, but additionally with a similar “speed of production and delivery that fast fashion retailers provide” under the widely-adopted mass production model.

But, first and foremost, it’s essential to look at the technologies currently in the market that have enabled advancements in personalisation.

Scanning technologies, mobile technologies and more

Hailing from Italy, ELSE Corp has a specific goal to ‘produce complete personalisation’ akin to that discussed within the industry and press, Golub says. At five years old, ELSE Corp (which acts as an abbreviation for Exclusive Luxury Shopping Experience) intends to innovate the fashion supply chain by forging a number of innovations including its own on-demand model for personalisation in design.

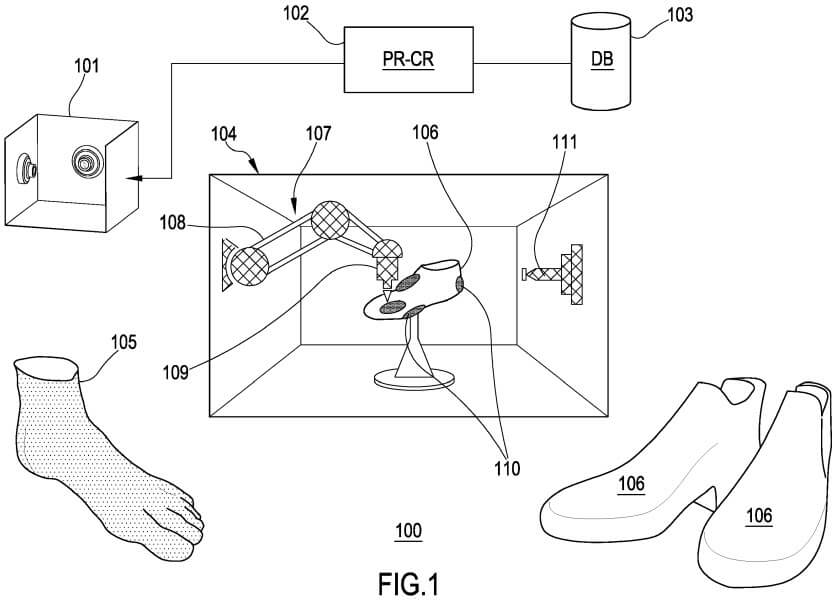

“The main goal [for ELSE Corp] is to develop new technology in an operational way and build a business model for fashion brands on how to connect design, consumer and manufacturing spaces to enable a real-time, interconnected supply chain,” Golub says with determination, referencing software that will enable ‘virtual retail’, whereby end-users can utilise the company’s cloud platform to personalise and design footwear on 3D technology, while 3D cameras help to create an individualised fit. Subsequently, the footwear is sent off via the cloud to be manufactured on a made-to-order basis – hitting back at overproduction, too.

Golub adds that most current personalisation technologies aimed at fitting are not quite refined, though, and only work as recommender systems.

“We work in the footwear industry. Everybody wants well-fitted shoes. Current [personalisation] technologies like fit scanners and mobile applications where you scan your foot – where some intelligent algorithm can recommend a size – only try to recommend a similar dimension to your foot. It will never be able to adapt [the shoe specifically] to you.”

Such companies utilising scanning technologies include Japanese knitting machinery manufacturer Shima Seiki and US e-retailer MTailor. At ITMA 2019 in Barcelona, the former announced its new MADE2FIT system, a smart programme able to scan the human body (with a smartphone app) and send subsequent data into a server, where bust size, waist size and ‘even sleeve length’ can be customised.

In an interview with WTiN, Shima Seiki’s media relations representative Masaki Karasuno said the system solves the homogeny of the basic ‘small, medium and large’ sizes offered by their on-demand WHOLEGARMENT machines by allowing the modification of the fit and drape of clothing. However, the report additionally adds that the technology is exceptionally suited to mass customisation, which highlights its use in traditional mass production models rather than individualised, on-demand ones. Although, this does present the idea that personalisation can occur at fast speeds, much like Galenytska predicts for the future.

Elsewhere, MTailor provides a similar offering. By downloading a smartphone app, end-users can order tailored formalwear. According to its website, the app uses a phone’s camera to measure a user – “in under 30 seconds, our machine learning (ML) algorithm measures you 20% better than a tailor,” the site says, citing a study conducted by the company.

In total, nine upper body measurements and seven lower body measurements are taken to create a custom fit, and although this successfully places personalisation tools in the hands of the end-user in a remote ecommerce environment, the garments take two weeks in total to be delivered within the United States, perhaps due to the company’s tailors being based in Bangladesh.

Additionally, US-based Size Stream offers 3D body scanning technology that captures over ‘six million data points’ around the user’s body in six seconds, for conversion into readable data that can subsequently produce a made-to-measure product. In an interview with WTiN, Size Stream also brought attention to the difference between size and shape with regards to personalisation.

“Measurements, by themselves, do not offer a clear indication of shape,” Size Stream told WTiN. The market may expect to see such technologies able to focus on shape – for example from tight or baggy fit to pear or apple shapes – in the future. An established example includes the aforementioned Shima Seiki technology, which allows the augmentation of garment draping.

Hurdles

Though these scanning technologies indeed advance personalisation, there are notable hurdles to overcome. First and foremost, turnaround time is visibly lengthened by tailoring, transnational manufacturing processes and delivery, while in other cases, only minor tailoring changes can be made due to its adhesion to traditional mass production models.

“[Other] companies offer made-to-measure, which means a complex, long process,” Golub says. Much like companies such as MTailor, where lead-times can be lengthy compared to fast fashion, made-to-measure processes (a main demand from end-users seeking personalisation) add considerable wait times to the design and creation process. “In the case of shoes, this would mean you need to make a custom last (the mannequin-like form on which shoes can be shaped and designed) which can be really difficult for a company.”

To meet both processes in the middle, ELSE Corp has tried to enable what it calls ‘industrial made-to-measure’: “This means that every order will be adjusted to customers, but it is still very close to one standard size. Our algorithm won’t just tell you which size to [purchase] but will recommend the product style (shoe last shape) that will fit you ideally.”

Golub continues to say that their technologies identify ‘made-to-measure zones’ on a person’s foot, which help to create an individual fitting profile. This means the company can use a ‘standard shoe last’, but to personalise the fit of the shoe, can add ‘millimetres’ of material to the ‘zones’ to extend the last beyond its standard shape, making an ‘almost perfect fit for a foot’.

“This is a high-value [service] for customers,” he says. “It is only order based.”

ELSE Corp’s goal is to provide retailers the option to hold ‘no physical inventory’ in a store, which may help to reduce overproduction, and more specifically, Golub says, a reduction in samples. All-in-all, end-users can utilise ELSE Corp’s 3D visualisation technology to personalise the design of a shoe (and “verify material choices, material combinations, etc”) while ‘3D cameras are used to inspect the user’ and build an appropriate profile with fitting ‘zones’. Manufacturers can subsequently produce made-to-measure footwear while customers receive a much more individualised product.

“Of course, the consumer will have to wait. You know, there’s a time [needed] to produce that. It’s not like tomorrow morning I can deliver you an industrially-made, made-to-measure product,” Golub admits. “It could [still] be very quick, it doesn’t mean like traditional apparel, where you wait six weeks or even months, especially now, with automation and a digitalised supply chain. [Overall], everyone can get what they want.”

But is personalisation at fast-fashion speeds just a pipe dream?

Distributed manufacturing

Technology trying to build the bridges towards speedy personalisation includes an offering from PAAT International (Purchase Activated Apparel Technologies), which utilises technologies such as automation and digitalisation.

Matthew Cochran, chief operations officer at the company, says the company’s software solutions may allow manufacturers to increasingly consider personalisation in their production processes while adhering to a new, on-demand modes of production that can also support speedy lead-times and ecological concerns by addressing overproduction.

While mass customisation and direct-to-garment print houses do not manufacture their garments on-demand, PAAT encourages garments to be made as-and-when they are ordered by the end-user – also known as made-to-order. To keep processes speedy, PAAT encourages distributed manufacturing within the fashion industry, and Cochran says this mode of manufacture supports companies, perhaps much like ELSE Corp, whose offering aims to further unique, more complex personalisation.

To summarise, PAAT collaborates with brands and technology companies to develop ‘Smart Tech Packs’, which are product-specific, machine readable files that contain “all the DNA to produce [their unique garment]”.

Essentially akin to the instructions in flat-pack furniture, PAAT’s Smart Tech Packs reveal a future in which manufacturing is an open, collaborative space and brands can employ the manufacturing skills of most, if not any, production facility around the globe (known as distributed manufacturing).

Subsequently, this allows brands to operate without being geographically locked. Since the customers of brands are often plotted sporadically across the globe, PAAT encourages on-demand, distributed manufacturing to give brands the ability to send Smart Tech Packs to manufacturers close to customers to improve production time.

Speaking with WTiN previously, Cochran suggested this technology is an enabler for personalisation. By removing the competition associated with partnerships between brands and their manufacturers (instead opting for a cooperative manufacturing model he titles coopetition), ‘better customer experiences can follow’. This mode of manufacture would likely cut down the lengthy lead times associated with the complicated manufacture of personalised products. This process also has the potential to cut away at environmentally damaging delivery processes associated with global shipping.

Additionally, exemplifying this move towards an open, cooperative and friendly manufacturing model is Adobe, Microsoft and SAP, whose collaborative project may also highlight new and upcoming personalisation technologies.

The previously ‘fierce competitors’ have since developed the Open Data Initiative, which, according to its website, allows ‘the knitting together of “data from any channel or device using a single data model to create a real-time customer profile”’.

This concept, if applied to the textile and fashion industries, could allow customers to have a cloud-based user profile that spans across connected manufacturers and brands, much like PAAT’s Smart Tech Pack.

Attached to this profile might be numerical information related to the user’s fit and shape, which would allow manufacturers to personalise the garment specifically for this singular user, Cochran suggests. Companies making strides in this field include OpenID and OpenSocial, who use open data platforms to allow profile-building.

This model would likely require an additional coupling with advanced technologies such as automation (for on-demand production) and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies (for an interoperable platform), otherwise found in the concept of smart factories.

For some, these technologies represent steps towards the development of advanced personalisation, which in turn seeks to quell fears of the loss of fashion individualism and the environmental impact of overproduction by turning to new modes of operation that revolve around on-demand, distributed manufacturing.

Although these companies continue to make strides with their innovative technologies, it is essential to gain insight from experts to determine the viability of new processes.

Perspective

Sophie Darby, digital innovation analyst at WTiN, says Industry 4.0 concepts such as this one have employed such innovative technologies that there is “significant potential for it to completely transform the industry and its supply chain”.

Following extensive reports into the technologies available, Darby additionally highlights micro-factories (a key development that can support distributed manufacturing), collaborative robotics and flexible manufacturing systems as innovations that support the spread of personalisation-based textile and fashion services while supporting rapid, on-demand production.

“There are companies working on integrating textile and apparel supply chain machinery and software specifically for the use in micro-factories,” Darby says. “Similarly, complete garment knitting is an innovative type of knitting machinery designed for mass customisation and is being led in the field by Shima Seiki and Stoll. One of the more interesting areas of opportunity is additive manufacturing and its potential if it became developed enough to quickly print garments of different textures and comfort.”

However, Darby adds that the implementation of personalisation faces a few hurdles globally: “Many of the largest textile and apparel supply chains in the world (ones that are offshoring production) will resist investing in these expensive manufacturing technologies because, when it comes to finances, it is not cost beneficial to replace inexpensive labour in countries such as Bangladesh, where workers are paid roughly US$95 a month to work 12-16 hours a day, seven days a week.

“Despite this, some companies such as Amazon – renowned for its 2017 on-demand manufacturing patent – contradict this.”

Darby concludes by suggesting that increasing developments in mixed reality (MR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies – similarly used among end-consumers alongside interactive technologies like 3D body scanning – may see rising investments from brands and retailers.

But as an industry, Darby says, “we are yet to see active movement towards true personalisation.”

Have your say. Join the conversation and follow us on LinkedIn