Geneviève Dion, director of Drexel University’s newly launched Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center at the Center for Functional Fabrics, explains how the 10,000 sq ft research and development facility plans to boost innovation in smart textiles. By Fiona Haran.

In September 2019, Drexel University opened its new renovated space for the Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center at the Center for Functional Fabrics. At the launch, president of Drexel University, John Fry, described the facility as a “place to engage, collaborate and lead innovation in the field of advanced manufacturing of functional fabrics”.

Located in Schuylkill Yards, an innovation district where researchers, start-ups and companies are “coming together to create and grow Philadelphia’s economy”, the new centre boasts 10,000 sq ft of mixed-use manufacturing, training and event space. The centre is funded in part by the State of Pennsylvania and by the federal government as part of Drexel’s involvement in the Advanced Functional Fabrics of America (AFFOA) initiative.

“We were one of the founding members of AFFOA, which gave us the opportunity to create the Fabric Discovery Center,” says Geneviève Dion, director of the Center for Functional Fabrics and the Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center.

Textile roots

Dion is a design scientist with an extensive background in bespoke clothing and industrial design. Explaining her involvement and the factors that led to the new centre, she says: “I started at Drexel University 13 years ago, and as a designer I was very interested in the materials and processes involved in the creation of smart textiles. I was given the opportunity to start a research initiative investigating the design and manufacturing of smart textile devices – we also call them ‘textile devices’ or ‘soft system devices’ now.

“This interest quickly led to the realisation that this field is very transdisciplinary, requiring people from many different fields to create textiles that can communicate, emit and transmit. They are very complex systems and to date, there are still very few products on the market. So, we realised that we needed to figure out how people can collaborate to make these textile devices a reality.”

Despite being under the same roof, the Center for Functional Fabrics (CFF) and the Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center (PA FDC) are said to have many differences. Explaining just some of them, Dion says: “The CFF works very much like academic research: we write grant proposals and we work with collaborators to create new materials, to innovate and research at the academic level. The PA FDC is interested in taking some of these discoveries to create products and work with industry partners, and to help move those innovations to products that could eventually be manufactured.”

And naturally, the primary aim of the two organisations is to solve some of the well-known challenges associated with functional fabrics. “We think about manufacturability, scalability and what equipment will be used, because I don’t want us to discover and create something that can’t be produced in large quantities. But, of course, functional textiles can’t just be textiles, they need to be textiles that can communicate, transmit and emit, and respond. Really, you’re trying to build these complex networks that include textiles as well as systems integration, communications and software development, and so on.”

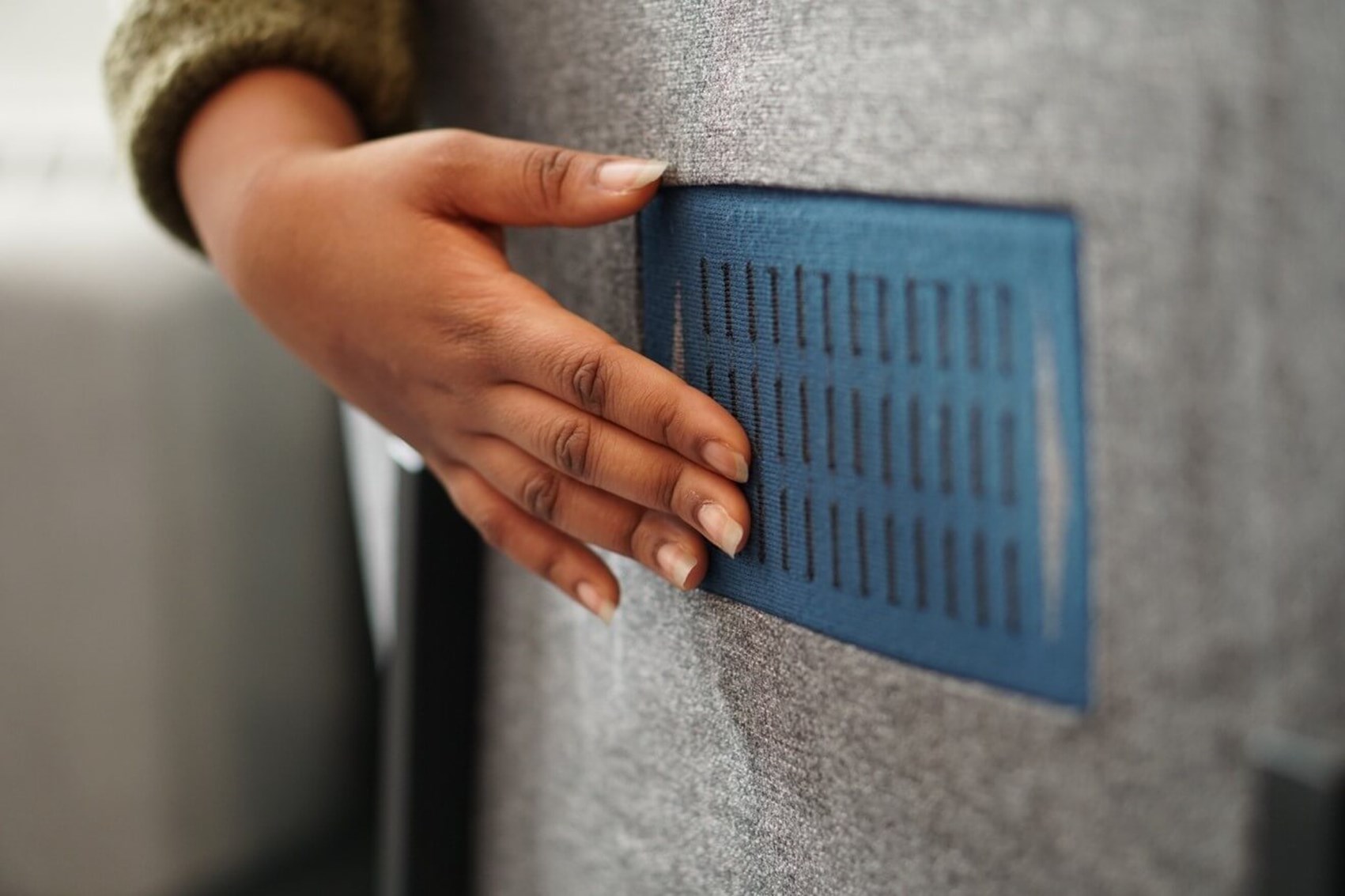

Drexel University co-op intern, Camren Randleman, tests out the Capacitive Touch Sensor (CTS) chair. The gesture sensitive functional textile touch-pad interface functions as a remote control for music, television etc

Work in progress

Drexel therefore seeks to identify production methods that advance the field of smart fabrics to create textile devices. Dion was able to discuss a couple of projects the centre is currently working on, which are said to be continuing projects over several years that are now starting to make some traction. One is a Capacitive Touch Sensor (CTS) – a functional textile touch-pad interface for physical devices. The CTS is produced as a single piece of fabric requiring only two electrodes to connect it to a microcontroller. It offers a solution for a flexible touch interface with consistent location detection, responsiveness, comfort and unobtrusiveness.

Outlining the project in more detail, Dion says: “One of the major challenges is connectivity of textiles to electronics … transmitting the data and processing the data. So, one of the things we aimed for in creating the Capacitive Touch Sensor is that, while we understand that we must have connectors, we can’t have hundreds of connectors because textiles and glue etc don’t get along. This then created another challenge which meant that the processing of the data we get out of a textile path had to be very robust. So, we aimed to have only two connectors. One of our PhD students has worked over the last several years to basically create a form of sensing that could be robust enough to do tap and gesture etc. From there, we’re now adding artificial intelligence research in order to create even more sensitive paths with an elegant design.”

She continues: “We’re trying to simplify textile devices so that they can almost become a component that people can add into other types of platforms. We can scale [the CTS] super large, put it on the walls, or make it super small to put it on furniture, garments or whatever else people imagine.”

As a proof of concept, the researchers have integrated the Capacitive Touch Sensor in a chair that could then become a remote control to control a TV or any other appliance in the home. “At this point we’re trying to show a variety of form factors, to show that it’s scalable – it’s a platform,” says Dion.

The manufacturing portion of the Center for Functional Fabrics also features a main equipment room outfitted for flat and circular weft knitting, warp knitting, weaving and yarn customisation. Explaining why this technology will prove so valuable for the ‘fabrics of the future’, Dion recalls the initial thought process that drove the idea back in 2007: “What I was trying to do when we started the research centre was to find a tool that could be ubiquitous and could adapt well as an advanced manufacturing platform. So, we chose 3D knitting because it is suited to prototyping and customisation, with similarities to 3D printing.”

She continues: “We could talk about robotic knitting and rapid prototyping … it was trying to make a segue so that, as a university centre, we were able to use our machines as instruments of research to demonstrate that we can rapidly prototype functional textiles. The set-up is difficult, working with the yarn is difficult, so to have a tool that is very versatile gave us the opportunity to demonstrate the integration.”

As Dion stated earlier on, CFF promotes working together, with ‘transdisciplinary’ research deemed a vital component in innovation. I asked her if she thinks that the gap between academia and industry is narrowing.

“I think that we’re much closer now, and I think that the world has really opened up in working together,” she says. "There’s much more understanding that [functional fabrics] is a very complex field. There are some products that are starting to come out. The machine makers are much more open and responsive now to the need and the desire for people to make technical textiles.”

The gap that Dion would like to see close, relates to software capabilities. “A lot of the software for textiles is graphics-based,” she says. “It’s extremely good at rendering what a textile will look like. But when it comes to having the physics and the information about the yarn and the bendability and resistivity of the yarn, that doesn’t exist. So, while you could go online and design an electrical circuit for microelectronics, you can’t do that with textiles. We are bound by the trial and error method. So, you could design a large amount of an aeroplane, for example, in a digital environment, and analyse it for stress and failure … you could do the same with a car, but you can’t do that with textiles. So, there’s a gap there that is starting to be addressed, and when we address that gap, that means that textiles can be really part of the digital fabrication that everybody is talking about,” she says.

Suggesting how the industry could solve this challenge, she says: “We’re going to have to mix textiles with other advanced manufacturing techniques, for example textile sensors with electronic devices … so, they have to be interchangeable. And that’s why some people are starting to use the term ‘soft systems’ as opposed to ‘textile devices’. I think that’s an interesting shift in words.”

As well as the change in language that the CFF hopes to achieve, Dion also highlights its aim to ‘change the perception of an old, dirty textile mill’.

“I think that we have an opportunity as a centre, because we give a lot of tours from young students all the way to government executives. We’re happy to show what we do, we welcome people to visit us, and we talk about the challenges associated with smart textiles and what progress is being made,” she says.

Fabrics of the future

Based on this progress, Dion envisions what the future of functional fabrics could look like: “For me, the future will be to create devices that are more like platforms so that they can be interconnected and talk to each other. An amazing current example of a platform would be the smartwatch that connects to the smartphone automatically – it’s not perfect but you can still go between Apple and Android devices. There’s still some clunkiness there, but at least there is a system of communication and protocol that’s understood. So, I think that textile devices can be part of that whole system, and that’s the part that I’m very excited about. But in order to get there, we have to be willing to address the grand challenges that we see along the way.”

That’s where the CFF comes in. “Being a centre that’s at the heart of the university, we have the opportunity to expose those challenges and to work with companies and academia to address them so that we can build a foundation of the field.

“As a designer you validate your product by putting it out there into the world and by getting customer feedback, to really understand what is needed. The centre has this broad vision and we find ways of showing what we’re doing through all of these different windows. And we have amazing collaborators that help us do that.”

Dion references a method that Drexel has developed to coat cellulose yarn with flakes of a type of conductive, two-dimensional material called MXene; this gives it the conductivity and durability it needs to be knit into functional fabrics. With this, the scientists say they are one step closer to producing wearable devices that are both functional and fashionable.

“MXene is a new material at Drexel that we’re trying to scale for textile production, so we sometimes seek partners who will help with that,” she says. “So, it’s more of a basic thing: how can we introduce that material in the yarn, how can we use the basic science that we’ve done? And then industry partners are always looking for new conductive materials, so that is one type of partnership we have. We have other partners who are actually manufacturers. With them, we take some of the textile devices that we’ve created and see if we can scale them up for large production. It goes through the full end-to-end of what we do.”

And through the new centre, Dion will be able to leverage her expertise in functional textiles and benefit from the results. She says: “It’s been a privilege to be a designer on all of these initiatives, and to bring a design and manufacturing perspective to the basic research. That’s the opportunity that I’ve been given at Drexel, that I’m very grateful for. Because of that, we’ve been able to create a place with a very different perspective and I hope that over time, that will show.”

To learn more about Drexel University’s Center for Functional Fabrics and Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center, visit https://drexel.edu/functional-fabrics/

Have your say. Join the conversation and follow us on LinkedIn