Will the Fourth Industrial Revolution transform flat knitting the way the Third Industrial Revolution did, or was it already here? Connie Huffa, co-founder of Fabdesigns, provides some insight.

Industry 4.0, IoT (The Internet of Things), the smart factory, and digitalisation of manufacturing are some of the buzzwords being used to describe how technology wizards are grappling with connecting the moving dots in many industries, including knitted textiles.

It’s true. There have been a lot of advances in our industry in recent decades regarding benchmarking best practices of producing products in better and more efficient ways, streamlining the design, and connecting supply chains with PLM, ERP and WMS systems. Linking the internal design and manufacturing departments with vendors and supply chains have been powerful game-changers in terms of organising manufacturing processes, which are needed to feed the mass-production monster that puts products in every warehouse and on every shelf.

In manufacturing, strategies for managing resources, components, and the production floor such as JIT (just-in-time manufacturing – 1970s), Kaizen (1985), Six Sigma (1986), ISO 9001 (1987) and LEAN manufacturing (2007), have all improved agility and profitability.

Getting closer and more focused on the end consumer and adapting to the pulse of buying trends have been key to many brands’ and manufacturers’ retail competitive edge. They leveraged retail data and built internal information channels linked from POS (point of sale) at individual store registers, which drills down to who is buying what, where and when. That information is then passed directly to warehousing and supply chain through Electronic Data Interchange, known in the industry as EDI.

EDI is a requirement to do business with most large retailers, and subsequently many small companies and brands struggled with the cost and expense of EDI, the inevitable charge backs, sales discounts and ‘allowances’, or were excluded from doing business with large retailers altogether.

Those businesses who could comply gleaned sales data, consumer demographics and purchase histories by store on a weekly, if not daily, basis. They could analyse, measure, and act on varying production, not quarterly, but weekly and monthly. This POS data gave a new agility to tailor merchandise assortments to regions and cultural groups, creating individualised store assortments based on consumer buying tastes. Smart companies utilise the POS and EDI data to design more product assortments that customers want to buy, and these companies then manage that development in Product Lifecycle Management systems (PLM). Product development feeds into a variety of other planning systems for operations (ERP), customer service (CRM), purchasing (MRP), marketing (MAS) and warehousing (WMS).

Just when manufacturing seemed to be a well-oiled machine, something happened. Around 2007, a new technology in the shape of a small rectangle with rounded edges and a flat black screen crept into the pockets of what is now over 2.1 billion mobile phone users all over the world. Taking pictures, communicating, banking, shopping and doing business online would never be the same again.

The internet became the main artery, connecting buyers from every corner of the world, sellers of all sizes, and commerce in small and large transactions. Consumers, especially young consumers, became digitally connected to real-time technology that gave them the ability to competitively shop in store or online, browsing thousands of items at hundreds of online sellers before making a purchase. The 2008 ‘bubble’, with restricted credit and tightened belts, taught consumers to spend wisely. Stores became showrooms, with customers checking features and quality but making purchases elsewhere.

2008 was a big year for bricks-and-mortar store closures due to the recession. A huge wrench was thrown into the gears of making and selling. Consumers could price products globally, and corporations could price materials, goods and services. The biggest shift in sales and marketing over the past five to eight years has been sales direct to consumers.

Since then, companies of all sizes experienced a shifting from wholesale relationships with bricks and mortar to online sales. Corporate relationships have been shifting from big buyers to individual consumers, meaning their accountability and accounting has swung to numerous small and individual transactions.

Why? Because each customer has a new voice in the new evolution of marketing (social media, influencers, product placement, celebrity), which has left traditional forms of marketing on the wayside with bricks and mortar.

Along with transaction types shifting, another thing has shifted – finance. Brands selling online have more of the MSRP (manufacturer’s suggested retail price) pie, and are paid before shipping, rather than waiting the 45, 60, 90 or 120 days that retailers leverage accounts payable.

Along with the injection of immediate cash, brands need to change part of their business model to sell individual units. Today’s consumer behaviours and expectations have changed dramatically since the recession, preferring online shopping to bricks and mortar, and expecting two-day shipping as a norm rather than a value-add as it was in the past. The same can be said for no-questions asked returns and real-time chat screen customer service. Today, about the same number of consumers prefer to shop in store as online, almost a ratio of 51:49. For millennials and younger people, it’s 67% preferring online, according to Entrepreneur Europe.

Price is key, but not as important as it was in 2008. Choice is more important to today’s customers, followed quickly by instant gratification. Consumers can flip through thousands of choices 24/7, anywhere they happen to be, with both thumbs on a 3-inch X 5-inch screen; getting the right product into consumers’ hands as quickly as possible. Time to customer has become a leveraging tool for both online sales and bricks and mortar.

In 2017, retailers closed more stores than in 2008, not because of a new recession, but because retail bricks and mortar found itself in a similar situation to all those roadside diners and motels in communities that prospered along Route 66 when the paved road bypassed them, and so did many customers. Some called it a ‘retail apocalypse’. In 2018, even fast fashion, once thought impervious to the onslaught of retail failures, is not immune.

Reacting to change

How are manufacturers dealing with this fast-paced, real-time customer-centric way of doing business?

In our textile industry the only constant is change. That is certainly true of fashion trends and our technologies. This whole system of making and selling as we have known it in the past, is becoming far more customer-focused, rather than product-focused, where customers have a strong voice in what they want and don’t want, using social media as a tool for that voice. Social media connects the end customer to sales and marketing and the entire manufacturing process, creating transparency, especially in supply chains. Consumers are voting for the products they want and don’t want, using social media as a platform for purchasing. Not since the era of individually-owned and operated shops at the dawn of the industrial revolution has the vendor been so connected directly to the end consumer.

In traditional manufacturing, an assembly line works on standard shifts to produce large quantities of products, which are then kept in inventory, typically in huge warehouses, until they are purchased. This whole process of make, stock and sell has been turned upside down. One could say that the entire value chain is in motion. The fundamental structure of every company that wants to compete in the new global marketplace is shape-shifting; a lot like the staircases in a Harry Potter movie. Consumers are connected. Some say consumer attention is the scarcest resource, and not every big company is doing it well. Makers who can respond quickly to the requests from consumers are succeeding. Manufacturers all over the globe with agile manufacturing systems and short lead times as well as quick production turns, are becoming sellers themselves, cutting out retail and going direct to consumers. If products are being stocked, for example in commodity products such as underwear, manufacturing partners and distribution centres are managing much thinner inventories, four to six weeks from point of sale. This means retail out-of-stocks and back orders might happen more frequently, should there be an unusual spike in sales.

Is there a new renaissance underway?

To keep up with consumer demand for high quality, low prices, instant gratification of online sales, and sustainability in manufacturing, no doubt our industry is facing major challenges. The challenge lies in creating a hybrid of tangible and virtual world in the hyper-connected IoT, which links big data, services, manufacturing, supply chain transparency, manufacturing automation, robotics in shipping, finance, and commerce data exchange. How? Our former systems, machinery, logistics and products are embedded with small chips or computers, which connected each to the other are storing pieces of information on where it’s been, how the product is made, when that product is to be made, and to where it’s going. The systems work together, utilising artificial intelligence (AI) to troubleshoot, move things around and complete tasks; all without human intervention.

In a digitalised manufacturing environment, everything is integrated and controlled with technology: data, R&D, marketing sales, purchasing, manufacturing, operations, distribution and customer relationships – a complete digital ecosystem.

In many cases, smaller companies have a significant advantage over large companies that typically have many layers of management and multiple divisions, where those designing things are usually disconnected from marketing and sales teams.

In today’s digital world, smaller companies can move faster with focused manufacturing, and they adapt to customers’ needs quicker by building and maintaining an online presence through blogs, influencers and social media – all things many big companies have taken a long time to embrace or have dismissed in the past as not contributing to traditional ROI models.

Small companies and individuals don’t need to purchase software to manage sales, EDI, distribution, commerce, or even customer service – four of the most expensive parts of doing business the old school way. Why? Because companies such as eBay, Amazon, Shopify, and Etsy, to name a few, have established platforms and standards for operations for entities big and small, wanting to sell direct to consumer. Big companies, as well as small businesses and individuals, can leverage these platforms that reach wide audiences of consumers and utilise the same big data. And for the most part, all entities are competing on pretty much a level playing field.

But is this an evolution? Or is it more of a revolution, a shift in consumer habits, in the same way those vintage neon road signs on Route 66 faded in the desert sun, while new big billboards along Route 60 directed customers elsewhere?

It’s both. Consumers are more educated about the products they buy. There is a new generation of consumers that only know recession, who wants to buy things that are durable. They care about where things come from and how they are made. When they like something, they tell everyone. When a product disappoints them, they tell even more people, as quickly as possible.

What are retailers doing?

Some retailers have set up their own online stores but find themselves competing directly with brands and discounters. Others are utilising existing platforms such as eBay, Amazon, Shopify and Etsy, and find themselves competing with small companies and individuals. Retailers that rely on having a physical presence are trying different things to entice shoppers, yet are using sophisticated e-tools to market, sell and deliver products. Companies such as Nordstrom are testing a smaller store, turning a 140,000 sq ft store into a 3,000 sq ft wine, beer and expresso bar, and providing other value-added services like stylists and alterations to entice customers, as reported by the Washington Post.

How are manufacturers dealing with this fast paced, real-time customer-centric way of doing business?

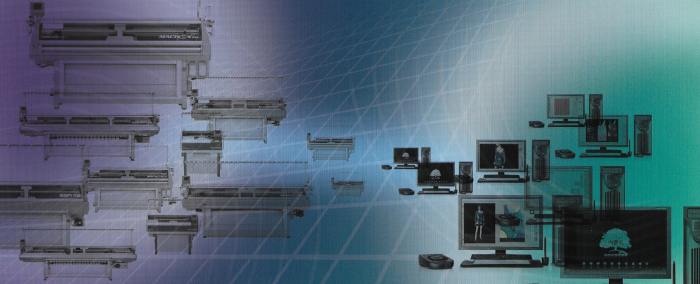

What’s most interesting about the technical changes happening in manufacturing since the recession is that new business models based on digitally-connected consumer expectations are evolving towards a complete digital network. In a digitalised factory there are two parallel universes, the manufacturing of tangible products and a virtual world that mirrors exactly what’s happening in that manufacturing process in real time. The machinery and people in the entire process are connected in a hybrid reality known as a ‘cyber-physical system’ (CPS). Along with demanding a new way of buying goods and services, this new generation of thinkers is generating new ways to look at textiles, considering how efficiently products are made, and combining material properties as multi-pronged, problem-solving solutions.

These new makers may not have deep experience in textiles, but they make up for it in imagination. The result: disruptive start-up technologies and groundbreaking technical textiles.

Many are utilising complete garment or complete product technology from machine builders to link automation in manufacturing with front-end data exchange to create small, focused smart factories. ‘Instapreneurs’ and on-demand manufacturing companies can literally manufacture and sell anything in only a few minutes. We’ve all seen the Etsy and Shopify success stories. This type of virtual designing, where a third party ships directly to the customer, is sometimes called ‘cloud manufacturing’. ‘On-demand manufacturing’ is scalable and involves adjustable production and assembly processes, where work is focused on putting together customised bundles based on real-time or current data from a client. The platform technology creates the ability to group many small orders together, keeping costs down for everyone and eliminating the need for minimum order quantities. All the intimidating engineering, complex manufacturing headaches, code writing, time-consuming back and forth and wallet-eating activities are streamlined in a platform that makes it easier, more agile, and far less expensive to make things. See https://macrofab.com/cloud-manufacturing/ for more details.

In the apparel industry, specifically knitting – there are a couple of standout companies utilising knit-on-demand, not as a limited promotion but on a commercial scale with real products that customers want. One is Ministry of Supply. It is said to be a “whole new way of thinking about manufacturing”, building beautiful garments with a very agile supply chain. Knitting to shape reduces waste to a bare minimum.

Another is Variant. (Disclaimer: Variant is a client of Fabdesigns, Inc). Variant has created a platform that allows individuals, brands, creatives, and anyone who wants to express their own creativity in fabric format to customise their own products online. They can even upload their own designs into the existing bodies. Brands can use the existing bodies with their own style guides or build their own templates which are pre-engineered and size-graded to work with the customising platform. That’s the front end, but the back end is equally impressive, with an automated knitting system in which no one must write programs, input graphics, or do any of the things a typical knitting factory must do to knit down a product. Production is streamlined and everything the customer inputs on the computer or mobile is designed, knitted out the back end seamlessly, and assembled with no cutting and zero waste. Variant currently has men’s and women’s garments in its cloud manufacturing library, but has shoes, bags and many other products planned in the next couple of months, as well as partnerships in the works.

A handful of shoe makers are enjoying success with on-demand automated manufacturing and transparent supply chains. One is Rothy’s located in San Francisco, which makes women’s ballet flats from recycled materials.

Another is JS Shoes, headquartered in Calabasas, California, which manufactures on-demand 3D slipper-shoes. The company is motivated by witnessing the long process, low efficiency, material waste, and poor working conditions of the traditional cut-and-sew shoe manufacturing system. Its shoe reduces 80% of the labour and 80% of the manufacturing process.

So, how does digitalisation of manufacturing affect the rest of our textile industry, specifically our knitting industry?

Actually, digitalisation of production is already available for flat knitting and has been for some time. It’s just that not every factory has found a return on investing in the digital production planning and control technology that was advantageous in the past. Many companies resisted investing in electronic knitting equipment when the Third Industrial Revolution took hold of our industry and pushed it to where it is today, by incorporating manufacturing with personal computers, the internet, and information and communications technology.

If we back up a little bit, in the late 1970s, about the same time JIT manufacturing was starting out, there was another technology shift underway. Most textile machinery and testing equipment were mechanical (analogue), and the first electronics were being introduced. At that time, manufacturing facilities had a competitive supply chain of able and willing yarn vendors, an education system that provided knowledgeable candidates to run our factories, and communities of skilled workers to support production. This was true of every sector of the textile industry, including our knitting industry. In the 80s, when computers first started making an impact, factories in the US and around the world were, for the most part, vertical. Design, management, sales, operations and logistics were predominantly under one roof. In the Americas and Europe, factories produced for their local markets, and only the largest exported around the world.

Computerised flat knitting machines, such as the Shima SEC and Stoll ANVH machines and CAD systems – including the Stoll VDU system and the forerunner of the Shima APEX system – gave designers and engineers creative control of their products beyond binary punch-cards. Adding computers to machinery gave mills an agility the mechanical machinery did not have.

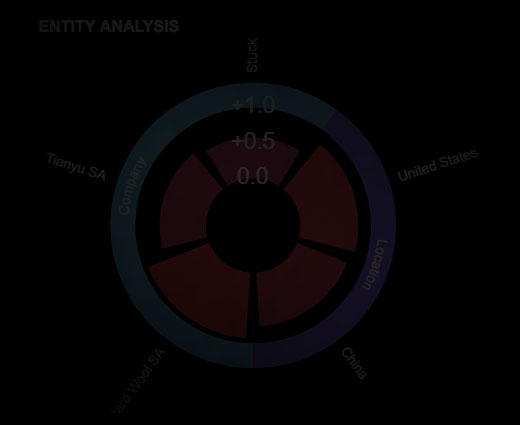

Shima KnitPLM applies a lot of technology with customers’ ERP and SCM systems for seamless linking of data between systems

Shima KnitPLM applies a lot of technology with customers’ ERP and SCM systems for seamless linking of data between systems

Those that didn’t update were left competing for low-end commodities. Those that did embrace new technology had a new universe of creativity opened up to them, where a complete non-repeating Jacquard could make up an entire garment panel. Some said the introduction of computers de-humanised products, pixelated them, and we’d lost craftmanship; but the computers came anyway.

The technicians (mechanics), who could literally hear how well or not a machine was running, felt that making things with computers was somehow cheating because the people programming didn’t have to understand how the machines mechanically worked. It was easier for them to visualise in steels or paste cards, rather than learn a computer system.

In 1987, the belt drive took over the knitting industry, allowing the machine’s cam box to knit only where the selection was on the needle bed. This was indeed a revolution, giving birth to those crazy multi-textured fabrics, the most famous being Coogi. While at the same time, many mechanical machine builders such as Dubied could not compete and faded away, along with the analogue factories and mechanics who couldn’t embrace the change.

In the 80s and 90s, flat knitting specifically, only a few companies such as medical companies, mass-customised products like children’s blankets, and high-end designer knitting facilities utilised the digital features of machine builder software that enabled automation of the entire production process, including sequential knitting, order compilation, order cueing, production and efficiency reports direct from each machine. For example: Shima Seiki uses a USB or a LAN cable to send information to the production machinery.

According to Paul Moore, a friend and colleague who is technical supervisor at Shima Seiki USA based in Monroe Township, New Jersey, who has been working on both Shima Seiki and Stoll machines for many years, “the Shima uses a system much like a server to a server, where there is no real limit to the number of machines able to be connected on the LAN. There is also SP3, which is a production reporting system. The SP3 is run on the server, managing and collecting data from the machines. Shima KnitPLM applies a lot of technology with customers’ ERP and SCM systems for seamless linking of data between systems. Workflow can be automated, depending on what customers need to make.” For more information, see http://www.shimaseiki.com/product/knit/plm/.

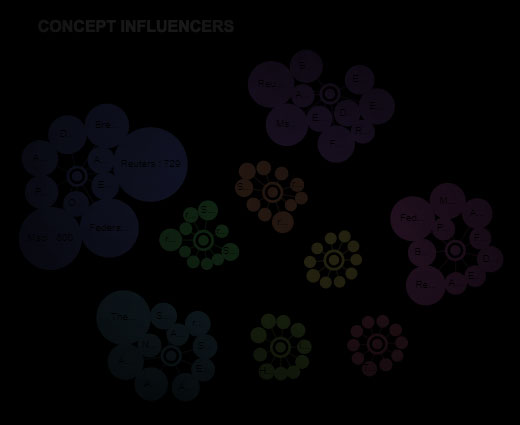

Flat knitting technology from Steiger

Flat knitting technology from Steiger

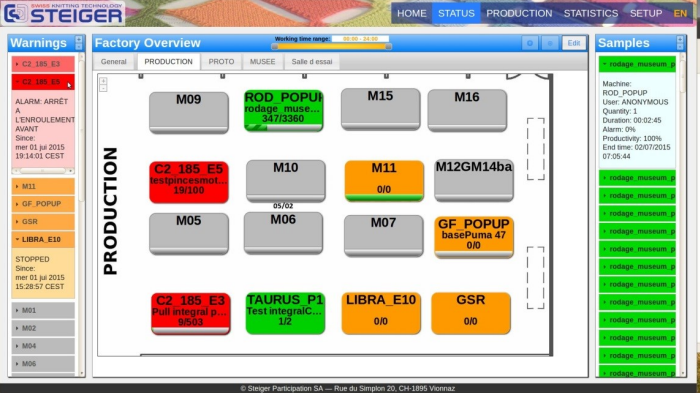

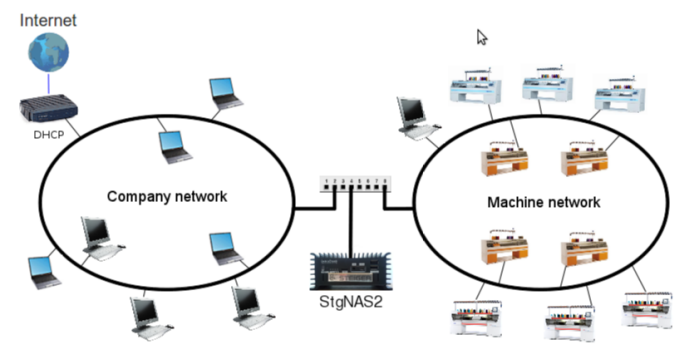

Jean-Luc Lepieszko, also a friend and colleague, senior sampling manager at Steiger Participations SA in Vionnaz, Switzerland, has worked on Steiger and Cixing machinery for many years. Speaking to us about the STGNAS2 system, he says: “You can prepare the production for all your machines, then the next machines, after finishing knitting its production, and see production, then load the next one. If there’s some changes to yarn or colour, you write an info. It comes on the screen of the machines, so the worker sees it and changes the colours or other requests. The machines can then start. If there is no change at all, the machine can start alone to knit. You can see all the values from production, for the whole factory, or for one machine, or one worker. You can put the name of each worker inside the system. All this value is saving production and error time. What kind of errors? There are a lot of default errors listed, but you can add some special ones which the workers must click on before starting to run the machine, and again after the machine stops. There are many more.” For more information, see http://www.steiger-textil.ch/.

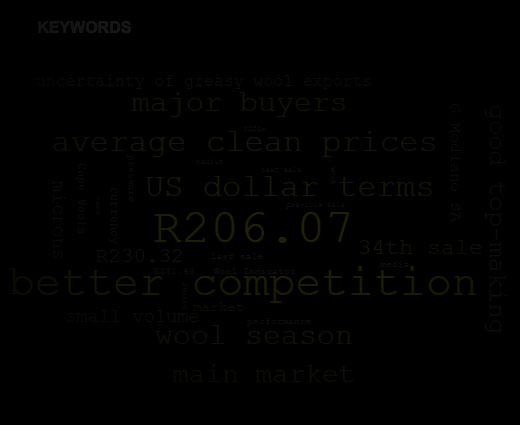

A digital factory overview of Steiger knitting technology

A digital factory overview of Steiger knitting technology

Stoll Knitting Machinery in Reutlingen has had a digital system in place since the mid-80s called a Selan, a computer itself, which buffered between the production machines and a computer using an ethernet cable network to link up to 128 machines. The computer system at that time was an Apple IIe, with at most one gigabyte of RAM. The networking system was also available on the later Silicon Graphics Sirix CAD system. Companies that utilised the full hardware and software systems offered by the machine builder were not only able to extract production reports collectively and individually through the Selan from each machine, but load programs, cue production, and boot machinery. Machines could pretty much run autonomously, fetching order programs sequentially from the dedicated computer through the Selan. Using one automatic software from the machine builder, a piece was completed by a machine, the machine ran slowly on empty knitting rows, while the computer oriented itself with the next order program in the cue.

Steiger's STGNAS2 system aims to save production and error time

Steiger's STGNAS2 system aims to save production and error time

In the 2000s, software like the one that ran through the Sirix, now runs on the M1+ system through an ethernet system to manage production on OKC. Today, there is a Stoll PPS system that manages and cues production for Stoll OKC and EKC generation machinery. For more information, visit https://www.stoll.com/_data/media/pdf/media_1726.pdf.

Industry 4.0

Today, we find ourselves amid a Fourth Industrial Revolution, where our industry is embracing robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), deep learning, nanotechnology, quantum computing, 3D printing, and the Internet of Things (IoT), all of which have the potential to connect billions of people and businesses around the world, improve manufacturing efficiencies, and transform the global economy. Now, as in the past, knitting machines need humans on the production floor to tie up yarns, fix broken needles, perform maintenance, and retrieve finished pieces. Everything else can typically be preloaded into the designated computer, cued and automated.

There were a couple of downsides to the automated systems that also seem true today:

1) Humans programming the system needed to have specific skill sets and knowledge of how to program complex functions in the machine’s language, (an example being Sintral for Stoll, developed by Thomas Stoll). There are few with these skillsets, because most apparel factories didn’t use those features in the past, and few use the whole system today. 98% of all knitting machines sold, regardless of brand, are still destined for apparel production.

2) Most systems can’t multi-task. In the past, if a machine needed attention and the software was busy elsewhere, the production machine would shut down, needing a human to intervene.

3) The computer systems of the past had limited RAM, (the Sintral language is based on the technology of circa 1978). Today’s systems may still use the machine languages of the past, but the power of computers, coupled with servers and smart devices, have given great power and agility to production planning and management.

4) It was important to keep machinery and machinery servers on an isolated system. This is much more important today, with so many viruses.

As with everything in life, there are positives and trade-offs to technological advances. Some of the positives of digitalising flat knitting manufacturing are:

1) Small makers can compete effectively, leveraging online marketing and selling platforms, while also utilising WYSIWYG machine builder software, producing in small microfactories, or perhaps not owning any manufacturing at all. In our industry people no longer need to know how to knit top make products with WYSIWYG.

2) Large companies may realise economies of scale, regardless of location, and therefore can ‘make’ closer to customers.

3) Tracking materials, processes, products, and performance in real time to gain insights for continuous improvement.

4) Transparency of supply chain and view of materials flowing through the manufacturing network.

5) Automation of redundant tasks that typically result in the most defects from human error and optimise factory operations to cut costs and improve efficiency.

6) Use of robotics and smart labelling in shipping.

7) Connecting finance and data exchange.

8) Developing data on customer preferences and making products customers want to purchase, by sending consumer experience data directly to project managers.

9) Today’s WYSIWYG machine builder software generates machine knitting programs. The same programs can be sent to networked production cues.

10) Workers on the floor do not need any programming skills to tie up yarns, change needles, and perform quality control (QC) and other basic maintenance.

The trade-offs being:

1) Large factories may not be as agile as several smaller factories that can be more flexible in serving local distribution.

2) Adapting to product changes in a completely digitalised factory is tedious. (Remember how challenging it is changing a variance in SAP? This is a similar situation).

3) Factories require designated lines for product/market-specific products.

4) Smart devices are needed for human interface throughout the system.

5) Streamlining products to fit into an automatic manufacturing configuration may also mean those products are not made as efficiently as possible. (Anyone who wrote Sintral knows that the WYSIWYG automatic CAD software from the machine builder is far easier to use than writing line-by-line code for sampling. However, WYSIWYG takes away control from the knit engineer, and the resulting prototype may not be the most efficient way to make production. So, the novice or the seasoned professional using the same library modules will likely produce equally inefficient programs).

6) Digitalising everything in a network may open vulnerabilities to unauthorised access to information and trade secrets.

7) Companies may lose control of their own data, as information is exchanged.

8) Most schools don’t teach knitting or textiles any longer. Therefore, without knowing how to knit, companies and individuals are reliant on the machine builders’ WYSIWYG software and stored libraries.

9) Everyone gets the same WYSIWYG machine builder library. Product designs need to fit into the parameters of respective machine builders’ WYSIWYG software.

10) For technical textiles, machine builder WYSIWYG libraries do not really apply. Therefore, knitting expertise is required to create products that are applicable to the specific market, and which are efficient.

The questions we as textile manufacturers should be asking ourselves are:

1) How might digitalisation disrupt my corner of the industry in the next five to 10 years?

2) Where is the value of digitalisation for my company?

3) What technology should my company invest in?

4) In what skills do we need to train our existing employees?

5) What talents should we be looking for in the future?

6) What happens if we do nothing?

As in the past, there is no one-size-fits-all for our industry, but one thing seems certain: as technology advances, consumers are demanding change. The days huge orders from big retailers may be numbered. AI will be a fact of life as countries race to automate manufacturing, the top three being South Korea, Singapore, and Germany. Automation levels the competitive field for products that are labour intensive, especially in countries with growing environmental and employee safety concerns.

Making our processes and machinery smarter, safer, better connected, more flexible, and more efficient seems challenging. However, if our profits are declining and consumers are demanding better quality products made quickly and customised to their preferences, along with enhanced customer service, and a transparent more sustainable supply chain, adapting Industry 4.0 into our processes seems a no-brainer to give the customer what the customer wants, especially if the digital technology already exists and has been a manufacturing standard for many of the best manufacturers in our industry for decades.

We can have confidence that we can all be prepared for the future. However, as connected customers of the machine builders, we ourselves need to be able to customise their WYSIWYG systems to meet our individual companies’ customer expectations.

Those who fail to connect our manufacturing needs to suit our customers’ wants will fade behind like the mechanical machines of the past.

Have your say. Tweet and follow us @WTiNcomment

RELATED ARTICLES

-

Using enzymes to enable T2T recycling in 2025

- Abigail Turner

- WTiN

-

Decathlon signs MoU to scale recycled polyester

- Abigail Turner

- WTiN

-

Recycled materials for flame retardant textiles

- Abigail Turner

- WTiN